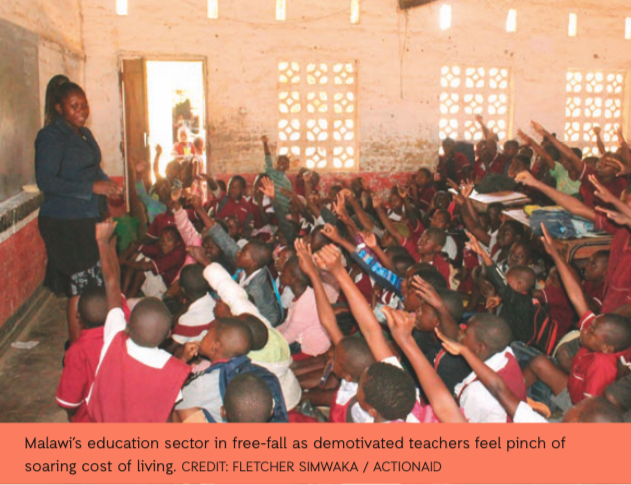

* Ms. Maluwa*, a Standard 5 teacher at Bumba Primary School in Rumphi District, dreamed of teaching as a way to uplift her family and inspire girls in her community to pursue education instead of early marriages

* However, after 14 years in the profession, she regrets her decision: “I now believe teaching is the least valued profession

* With over 200 students in my class and inadequate teaching and learning materials, delivering quality education is nearly impossible

Maravi Express

ActionAid International, in its recent research released this month, entitled; ‘The Human Cost of Public Sector Cuts in Africa’, — drawn from a survey conducted through interviews and focus group discussions in six African countries, Malawi, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia and Nigeria — dives in-depth of challenges being faced in these debt-ridden countries.

Advertisement

For Malawi’s case, ActionAid International describes the education sector being in a crisis as demotivated teachers struggle with impact of austerity measures as follows:

Ms. Maluwa*, a Standard 5 teacher at Bumba Primary School in Rumphi District, reflects on the disparity between her aspirations and the reality of her profession.

Growing up in Wenya, Chitipa District, she dreamed of teaching as a way to uplift her family and inspire girls in her community to pursue education instead of early marriages.

However, after 14 years in the profession, she regrets her decision: “I now believe teaching is the least valued profession,” she laments. “With over 200 students in my class and inadequate teaching and learning materials, delivering quality education is nearly impossible. Monitoring individual performance and supporting struggling students has become a daunting task.”

Maluwa* explains how the school is forced to ask parents to contribute money for school expenses and examination paper production, putting additional strain on families already struggling financially.

This, she says, undermines the goal of education for all, as students from poor households often drop out. Parents, unable to afford these fees, are forced to make heartbreaking decisions, often prioritising boys over girls.

“In some cases, girls are forced to give up on their education dreams,” she says. “Yet, as a school, we desperately need these contributions to buy necessities like charts, dusters, and chalk, and to conduct quality examinations.”

Efforts to seek support from district education authorities have yielded little success and Maluwa* attributes this lack of response to the Government’s shrinking fiscal space caused by growing public debt.

“The debt crisis has intensified calls for public expenditure cuts, severely affecting education and other essential sectors,” she explains.

Advertisement

The devaluation of the Kwacha has driven up the cost of essentials like food and fuel by over 100% since 2023, while her salary has remained stagnant. This has forced her to take on additional work, such as running a grocery shop, to make ends meet. “Life is becoming unbearable. Frequent devaluations of the Kwacha, without salary adjustments, are pushing me closer to poverty,” she adds.

Maluwa* urges the Government to abandon austerity measures and prioritise saving the education sector. She calls for engaging international financial institutions for debt relief to create fiscal space for investment in education and health.

“Once the Government addresses these challenges, it can employ more teachers to reduce the teacher-pupil ratio and provide adequate teaching and learning materials to ensure every child can stay in school,” she concludes.

ActionAid further unpacks the serious challenges in these six countries that were surveyed:

Worsening Pay and Conditions, and the Ripple Effects on Teachers

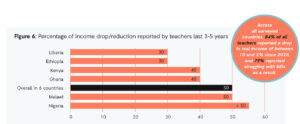

Teachers are facing a financial crisis, with declining wages eroding their quality of life, particularly in the context of high inflation. 84% of all teachers reported a drop in real income of between 10 and 50% since 2020, and 79% reported struggling with bills as a result.

Many have been forced to explore additional income streams, with 47% attempting to start small businesses to make ends meet. 70% reported negative effects on their children’s education, and most have had to cut back on food and rent payments (60% and 79% respectively).

The resulting strain is felt deeply, with 89% of workers citing mental stress, further compounding the pressures on their professional and personal wellbeing.

The country-specific situation shows that the number of teachers reporting a decline in wages was highest (more than half) in Nigeria (Figure 6). The impact is evident across all countries, as teachers struggle to: pay their bills (96% in Kenya, and 79% in Nigeria); pay for their children’s schooling (90% in Malawi, 81% in Ghana); or have noted impacts on family food intake (97% in Liberia, and 91% in Ethiopia).

70% of Kenyan teachers surveyed reported having to start small businesses in order to make ends meet, as did 65% in Ghana, but only 9% of Ethiopian teachers.

Deterioration of Working Conditions

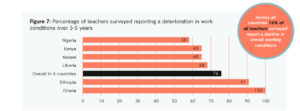

Beyond financial hardship, the working conditions for education staff have steadily worsened. Extra responsibilities, growing class sizes, and the behavioural challenges of students have pushed 76% of all surveyed teachers to report a decline in overall working conditions (Figure 7).

The highest incidence of deteriorating working conditions was in Ghana (100% of respondents) and Ethiopia (91%), compared to 58% in Nigeria (Figure 7).

Dwindling Access to Professional Development

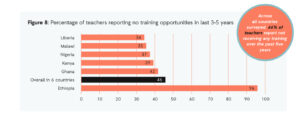

Access to professional training is dwindling across the six countries, with 46% of teachers not receiving any training over the past five years (Figure 8). Men (67%) have greater access to professional development opportunities than women (44%), and urban workers (66%) fare better than rural workers (45%).

Training opportunities have declined particularly for rural workers and women. While some improvements in training quality have been noted (67%), access remains unequal, limiting opportunities for professional growth.

Ethiopian workers were the hardest hit, with 96% reporting no professional training opportunities in the last 3-5 years (Figure 8), and 100% reporting that the training available was of poor quality, compared to 34% of respondents in Liberia.

Challenges in Achieving Work-Life Balance

The growing demands of the job, and the decline in pay and conditions, have left many teachers struggling to maintain a work-life balance.

Over 52% reported increased workloads in the six survey countries, yet 94% say they received no extra pay for the additional responsibilities.

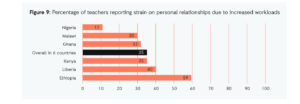

This imbalance is straining personal relationships for 40% of workers (Figure 9), and many are contemplating career changes.

Teachers in Liberia (79%) and Kenya (78%) reported the heaviest workloads, and reports of this causing strain on personal relationships were most pronounced in Ethiopia (59% of respondents) and lowest in Nigeria (11%).

Most respondents across the survey countries highlighted the lack of fair compensation for the additional time they were compelled to work.

Constraints on Support from Teachers’ Unions

Unions serve as a crucial support system for public teachers, providing support such as pay negotiations and legal aid. 82% of all teacher respondents reported membership of a professional association or trade union, with women reporting a higher membership rate (86%) than men (77%).

Rural workers benefitted more from pay-related support (46%), while urban workers reported greater access to legal assistance (44%). 100% of respondents from Ghana and Nigeria reported membership of teacher unions and associations, and 95% in Malawi.

Advertisement

These unions have been instrumental in securing pay raises, with the highest reported support in Malawi (58%) and Kenya (50%), compared to only 6% in Ethiopia.

Union support for obtaining long-term contracts was most frequently reported in Ghana (45%) and Kenya (33%). Legal assistance provided by unions was reported most in Ethiopia (78%) and Kenya (67%), in sharp contrast to Nigeria, where only 11% of respondents reported receiving such support.

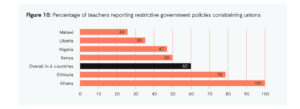

However, unions face significant challenges in their operations, including restrictive government policies, as was noted by 60% of respondents overall (Figure 10), while 46% noted funding limitations. 100% of teacher respondents in Ghana and 78% in Ethiopia identified restrictive government policies as a significant barrier to the effectiveness of unions.

This was also noted as a problem by half of respondents in Kenya, and 47% in Nigeria, although in some countries, such as Malawi, this was considered less of an issue (26%) (Figure 10).

Even though there may be global forces and trends, the diversity of country responses to this question demonstrates that decisions around civil and political space still lie largely with national governments.

Teachers Leaving the Sector

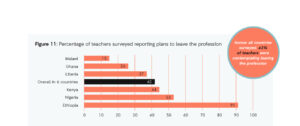

Overall, in the six countries surveyed, nearly 42% of teachers were contemplating leaving the profession altogether (Figure 11), although 85% said they would stay if pay and work conditions were improved.

Ethiopian teachers exhibited the highest level of dissatisfaction with their jobs, with 91% expressing a strong desire to leave, followed by 53% of Nigerian workers, 44% of Kenyans, 26% of Ghanaians, and 15% of Malawians (Figure 11).

However, most of these workers would consider staying if there were improvements in their salaries.